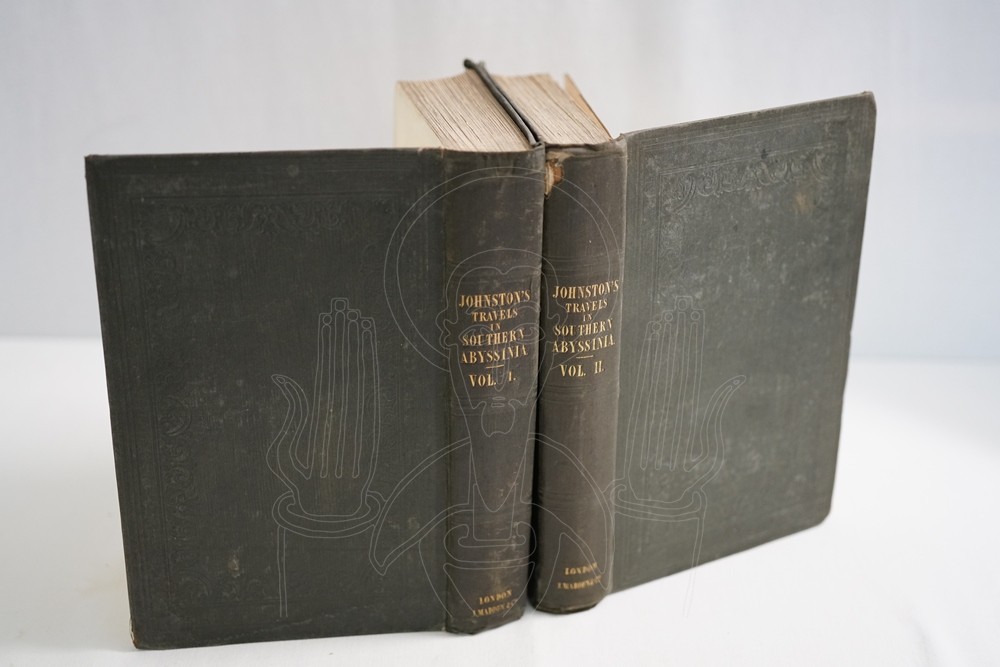

Travels in Southern Abyssinia, through the Country of Adal to the Kingdom of Shoa

Édition

Éditeur : J. Madden and Co.

Lieu : London

Année : 1844

Langue : anglais

Édition : première édition

Description

État du document : bon

Références

Réf. Biblethiophile : 002946

Réf. Pankhurst Partie : 1

Réf. Pankhurst Page : 123

Réf. UGS : 0184203

Première entrée : 1842

Sortie définitive : 1843

COLLATION :

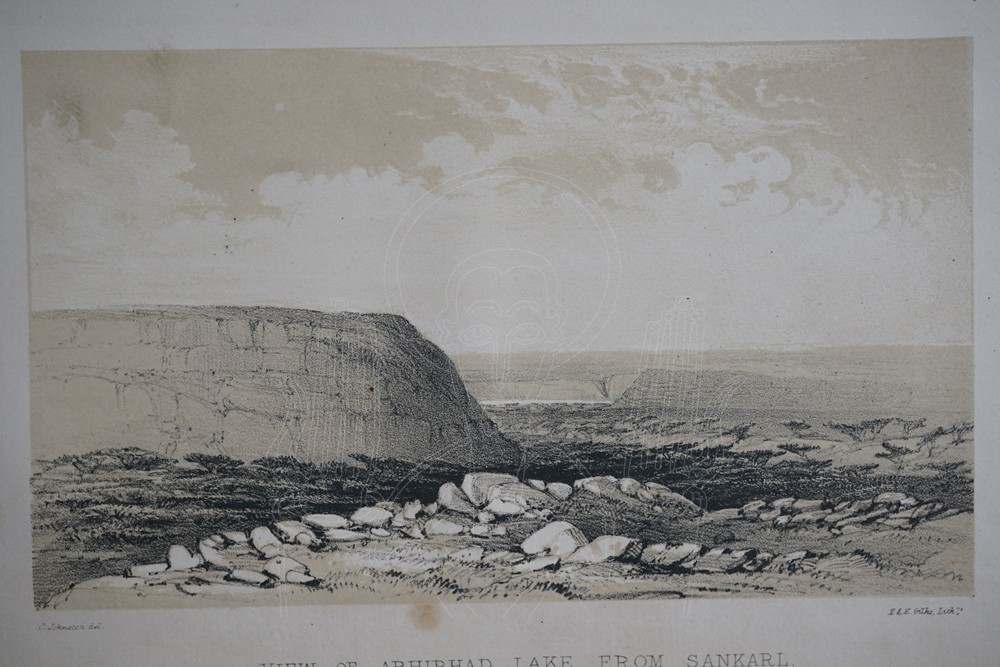

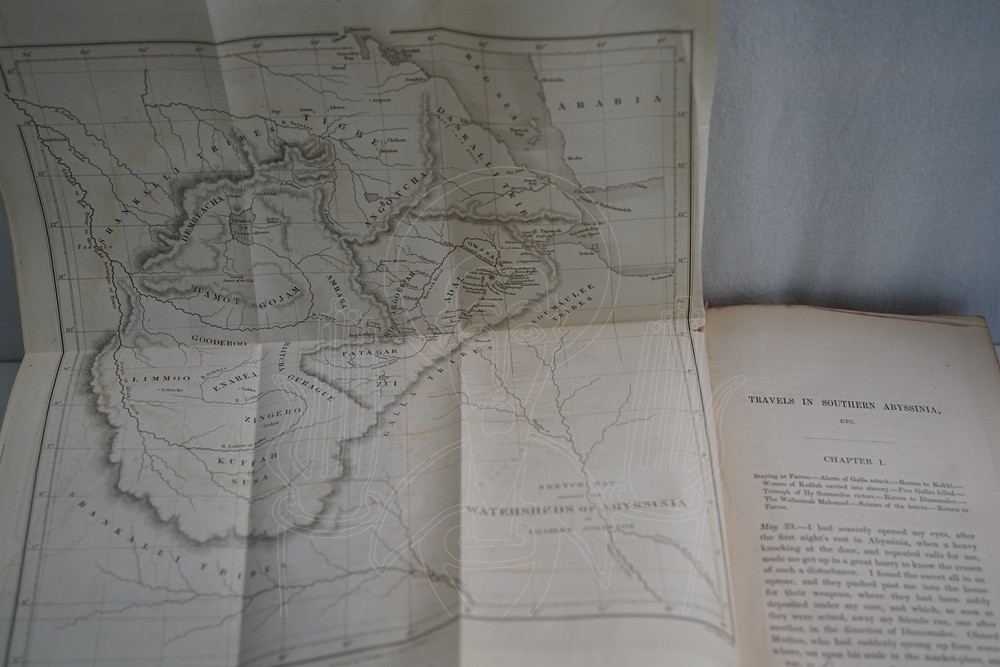

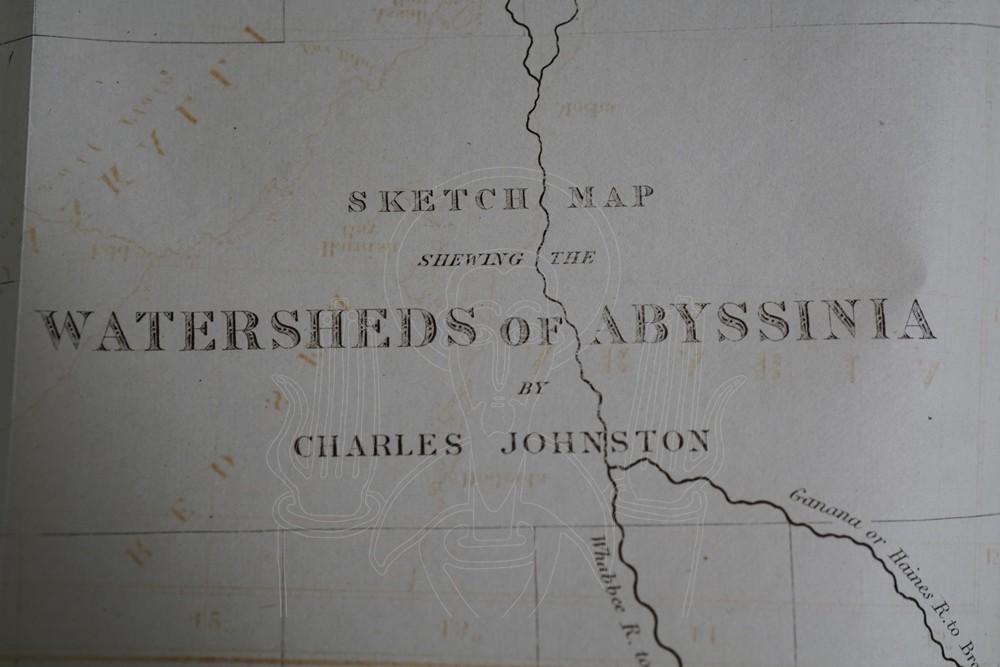

Octavo, XVI+ 492 pp., VIII + 447 pp., original cloth, 2 volumes (complete). Folding map + 2 tinted litho frontispieces, 8-page advertisement at end of second vol. dated December 1843. Hinges professionally repaired, cloth worn through at tips, crown of vol 2 chipped, marginal dampstain to first few leaves of vol. 2, each title-page with the embossed owner's stamp of "Leonard G.". Rare. Only 5 auction records in the last 30 years (2015). Brunet VI, 28021, not by Henze.

En savoir plus

Les tribulations d’un médecin écossais

Charles Johnston (1812-1872) est engagé comme médecin sur le Phlegethon et se retrouve à Calcutta au mois de mai 1841. Au même moment, le navire qui emmène l’ambassade britannique au Choa conduite par le capitaine William Cornwallis Harris mouille à Tadjourah. Nourrissant depuis deux ans le projet d’explorer le continent africain, il profite de l’opportunité et obtient la permission de la rejoindre[1]. Cependant, il n’arrive à Aden que le 24 décembre à cause d’une fièvre contractée à Bombay qui, d’ailleurs, compliquera son séjour au Choa.

Pourtant accompagné de Hatcheloor, la première tentative ne lui permet pas de débarquer à Tadjourah et il se trouve contraint de se replier sur Aden. Peine n’est pas perdue puisqu’il y rencontre le lieutenant William Charles Barker, de retour d’Aləyyu Amba, rappelé par ses supérieurs à Aden. Johnston est par conséquent mis au courant des difficultés qui l’attendent, autant de la piste qui mène au Choa que de l’entrée dans le royaume.

La deuxième tentative, par Berberah cette fois et conduite par Cruttenden, est couronnée de succès le 4 mars 1842. Le 27, la caravane quitte la côte, atteignant Bahr Assal le 5 avril, l’Awash le 20 mai et trois jours plus tard Fārrē. Le lecteur peut refermer le premier tome.

Un ouvrant le second, il apprend que Harris a envoyé Robert Scott – Surveyor and Draftsman de l’ambassade – rejoindre Johnston. Le 31 mai, lassés d’attendre la moindre manifestation du negus Sahlä Sellase, ils prennent l’initiative de se rendre à Angolala, sans sauf-conduit royal et en faisant une halte à Ankober où sont cantonnés les deux Allemands de l’ambassade : le médecin Johannes Rudolf Roth et le peintre Johann Martin Bernatz.

Dès leur première rencontre, le courant ne passe pas entre Johnston et Harris. L’auteur ne craint pas de s’en expliquer ouvertement :

Unfortunately, amidst all his kindness, Capt. Harris considered it to be his duty to take notes of my conversation, without my being aware in the slightest degree of such a step, or being conscious of the least necessity for his doing so. On my becoming aware of this circumstance, a few weeks after, by the distortion of a most innocent remark of mine, which was imputed to me in a sense that I never dreamt of employing it, I retorted in a manner that led to further proceedings; and from that time all intercourse between the members of the Embassy and myself ceased for some months[2].

Confinement

Les conséquences se seront pas sans incidences pour Johnston car, cloîtré à Aliu Amba, entre Ankober et Fārrē, il ne peut compter que sur ses propres ressources pour répondre à ses besoins et pour surmonter ses crises de fièvres.

Comprenant que Johnston est indépendant de l’ambassade, le Souverain accepte de le recevoir. En retour, Johnston cherche à se rendre utile et à apprendre l’amharique, ce qui confère une saveur toute particulière à ses descriptions des us et coutumes de ses hôtes.

John Airston

Tout comme Johnson, Airston est écossais, né en 1812 et caresse le projet d’explorer l’Afrique. Ce qui les différencie notoirement, c’est qu’Airston est mort à Fārrē il y a deux ans. Barker et Johnston sont en définitive les seuls sources primaires et fiables pour tenter de retrouver la tombe de l’infortuné.

Dans un premier temps, dans une note, Johnston présente son compatriote et sa fin tragique :

This gentleman, after having passed through all the dangers of the Adal country, was suddenly attacked with inflammation of the brain at Farree, where he was awaiting the permission of the negoos to enter Shoa. He died after a few days’ illness, during which time M. Rochet d’Hericourt and Mr. Krapf rendered every available assistance.

Ensuite, il raconte sa visite de la tombe :

Some months after I had lived in Shoa I visited the Wallasmah, on purpose to see the state prisons of Guancho. I remained all night, and in the morning was taken to a ridge opposite, towards the south-west, where stood a small » Bait y’ Christian, » the church of St. Michael’s in Ahgobba. I felt pleased, when I reached the spot, that the object of my attendants was to point out the grave of my deceased countryman, which, with natural good feeling, they had supposed would be interesting to me. To give Mr. Airston Christian burial, the kind-hearted people of Farree (Mahomedans) must have carried his corpse more than six miles over the roughest road imaginable[3].

Dans un second temps et dans le texte cette fois, Johnston aborde la prison d’état de Guancho :

The Shoan prison for these unfortunates [the other branches of the Royal Family] is a high conical hill, called Guancho, situated midway between Aliu Amba and Farree, and is the residence of the Wallasmah Mahomed, who fills the office of State gaoler, as well as collector duties upon that frontier of the kingdom. Here, at the period of this interview with the King, were confined five princes of the blood Royal, some of whom had been prisoners for as many as thirty, or thirty-four years.

En apportant des détails inédits sur les lieux :

From personal inspection of their apartments, an opportunity afforded to no other European besides, I can state that the close and rigorous confinement, said to have been imposed upon these captives, is much exaggerated; and, although the separate sleeping apartments at night were not more than seven feet in all their dimensions, still they were only composed of sticks, such as the common garden rods for raising peas in England, and a strong man leaning hard against them must have fallen out through the wall of his cell.

Puis sur les prisonniers :

Only two of the royal prisoners wore chains; these were on one hand and leg of the same side, and were long enough to admit of the freest motion. Along-thatched wort bait, or meat house, contained their families; for not only did the King remember his captive brethren on days of festival, by sending them oxen, and honey-wine, but they were allowed to marry, and their wives lived with them in their confinement.

Finalement, Johnston livre des précisions sur les environs de la prison :

I took a ground plan of the whole establishment, and the Wallasmah, who was too old to accompany me on my survey, when I was in the only place that looked like a dungeon at all, a vault about twenty feet square, cut out of the summit of the hill, stamped several times upon the roof to intimate that his sitting-room was over this secure place. In this dismal dungeon, however, no person had been confined for the last six or seven years, although it was being then prepared, by a second door being put up, for the occupation of the unfortunate Samma-negoos, an ex-frontier governor, who had assisted his brother, a denounced rebel, to escape to Ahgobba, where he is now entertained by the Mahomedan Prince of that country, Beroo Lobo. When I visited Guancho, this prisoner occupied a small den of sticks, not four feet wide in any direction, and his hands and feet were chained close together, so that his removal to the larger subterranean cell will, at all events, afford him some opportunities of exercise, though he will then be deprived of light and fresh air[4].

Il n’est pas ici le sujet de traiter ces renseignements qui auront meilleure place dans l’article réservé à John Airston et à celui consacré à Gončo. Revenons au séjour de Johnston.

La fièvre

Malheureusement pour le lecteur, le 3 septembre 1842, à Aliu Amba, Johnston met abruptement un terme à son récit, arguant que la fièvre le confine à son lit et que son journal se résume à une série d’entrées du type : « no better to-day ». Cette fin en queue de poisson ne doit pourtant pas nous surprendre car également Harris reste muet sur son retour en Grande-Bretagne.

Quel est le fin mot de l’histoire ?

La note de bas de page 381 révèle que Johnston est retourné d’Abyssinie en compagnie de la British Political Mission. Est-ce par honte d’avoir rejoint l’ambassade qu’il s’abstient de terminer dignement son récit ?

En fait, cette fameuse note mène à l’article d’un voyageur anonyme qui relate son départ de Fārrē pour Tadjourah, le 10 février 1843, en compagnie du capitaine Harris et d’une caravane d’esclaves, au nombre de 130 ou de 140[5]. Le reste du texte est confondant et peut être considéré comme une charge affligeante pour Harris et la mission elle-même. Mais aussi incompréhensible que cela puisse paraître, dans l’introduction à la seconde édition de The Highlands of Aethiopia et pour se défendre d’une traduction, Harris renvoie ses lecteurs vers le même article[6]. Il ne fait aucun doute que Johnston est l’auteur de cet article.

Mis à part le contenu de l’article anonyme, abjecte aux yeux modernes, on peut en tirer la date du 15 mars 1843 pour l’arrivée de la caravane à la côte. Mais elle n’a désormais plus beaucoup d’intérêt, l’esprit étant ailleurs.

Avant de terminer, permettez une question.

De quoi parlent Beke et Johnston lorsqu’ils se rencontrent à Djedda au mois de mai 1843 ?

Cela n’a pas été consigné mais, au Choa, Harris a dû avoir les oreilles qui ont sifflé.

Biblethiophile, 16.10.2025

[1] JOHNSTON (Charles), Travels in Southern Abyssinia, through the Country of Adal to the Kingdom of Shoa, p. 1

[2] Ibid., p. 64.

[3] Ibid., t. 1, p. 485.

[4] Ibid., t. 2, p. 419.

[5] Anonyme, « The slave-trade in Abyssinia : a personal narrative », The Anti-Slavery Reporter, November 29, 1843, p. 221-222.

[6] HARRIS (W[illiam] Cornwallis), The Highlands of Aethiopia, note 1 en bas de page xli.